This is dedicated to everyone who ever looked at a Datsun 510 and saw

a BMW.

This is dedicated to everyone who ever looked at a Datsun 510 and saw

a BMW.

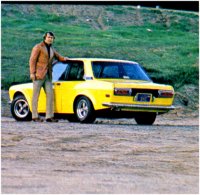

It is a story of people, men like Nissan US president Yutaka Katayama, style-setter Sergio Pininfarina and Datsun racer Peter Brock. And it is a story of a car, a very special car remembered fondly now as the "Screaming Yellow Zonker."

Some background. Deep background. Go back to a time when Japanese cars were considered "tinny", when their useful lives were thought to end at 30,000 miles, if not before. To a time when the Japanese were so out of synch with the automotive currents that when the rest of the world was trying to decide whether a sports car should have two seats or four, the Japanese gave us one with three (the Datsun 1500).

Then, change. In 1967 Datsun debuted the 510, a redesign of its aging and distressingly conventional 411 model. Looking back, it's easy to see how significant the 510 was to the evolution of the Japanese car. It was the first modem Japanese sedan, perhaps the first car to reveal why years later the audience for Far Eastern autos would be comprised of more than ex-Dauphine and Beetle owners.

The difference between the 510 and other Japanese cars is well-illustrated by a comparison with its predecessor. The 411 was odd-looking in the Japanese way, and its engine was filled with pushrods, its suspension leaf sprung. Overall, it was a good 10 years behind the times.

By contrast the 510 was almost European-looking -- Certainly the most modern appearing Japanese car of its day. Power came from a sohc 1.6 liter four with almost one hp per cubic inch. Its suspension was fully independent. All for $1996.

Imitation was the key. For the 510, Datsun scanned the automotive world and either hired the best people, or copied the best designs. Little known at the time, for example, was that the fabled Pininfarina style house had been hired to create its gracefull lines. (Not that even Datsun fully saw the genius in this; the 510 was followed by the 610, 710 and F-10, each more appalling than the one before).

For engineering, Datsun looked to Germany. In addition to its sohc engine, its suspension featured MacPherson struts in front, semi-trailing arms in back-a common arrangement now, but in 1968 only commonly associated with BMW 2002s. (Hence, the 510 came to be known as "the poor man's BMW. ")

Not that it much handled like a BMW the 510's skinny original equipment tires were hopeless. But the potential was there, and Datsun recognized it. Especially Katayama, who saw that performance was big in the US, that Datsun wasn't, and decided the company should go racing.

Enter Pete Brock, he being something of a Southern California phenomenon. In his teens, he made it into the prestigious Art Center College of Design on the strength of a few pencil sketches on notebook paper. After stints with GM and Carroll Shelby, for whom he designed the world-beating Cobra Daytona Coupe, he formed BRE-Brock Racing Enterprises.

About BRE it could be said that it was perhaps the best racing team that never quite made it to the big time. Its dreams of Indy and LeMans were never realized, but its success for Datsun in SCCA C Production, and B and C Sedan categories is the stuff of legends. In these and the under 2.5 TransAm class, BRE built a dynasty.

It was an inspired concept; the inexpensive Japanese car laying waste to all those purebred 2002s and Alfa GTVS, then the darlings of the sporty car set. Never mind that the BRE cars in some cases cost far more than the Alfas or BMWs -- that's racing. Never mind that the team was comprised of a veritable all-star line-up of mechanics and engineers, or that ace driver John Morton was assisted on occasion by the likes of Bobby Allison and Peter Gregg. The Datsuns made their point.

It was during these years that the BRE team, heady with its seemingly limitless success, decided it should have a parts chaser car around its El Segundo shop. A Datsun, naturally, but not just any Datsun.

On to a standard 510, then, went whatever bits were lying about. Race car bits. On went a fiberglass hood, trunk and fenders. In went a rollbar-just like the race car's-and a BRE racing seat and harness.

The suspension obviously couldn't be pure race car, but it had a lot of the same touches. Shorter, stiffer springs were installed. Mounting points were relocated to facilitate lowering. A rear sway bar was added, as well as a thicker one in front.

The engine was blueprinted and fitted with a semi-race cam, headers and full race forged pistons (creating a compression ratio about 47: 1). Output was about 130hp.

Perhaps most stunning was the car's color, a pure "process" yellow specified by Brock himself. (Brock created the "LeMans" stripes and other paint schemes popularized on Shelby Mustangs and Cobras, as well as BRE graphics.)

The Zonker was a hit. Instantly it became the ideal upon which hundreds, perhaps thousands of privately modified 510s were based. It was the subject of a 1973 Motor Trend article and even the basis of a Revell plastic model kit. A star.

I owned the Zonker, briefly, in 1980. I had to have it, such a 510 zealot was I. I located it in Virginia through an AutoWeek ad. It was rust-free and startlingly original, down to its Goodyear Rally tires (albeit with tread worn to invisibility). The original paint, cracked in places, still gleamed.

On the drive back to Detroit it performed flawlessly, which is to say that it was spry and could run rings around any sports car of the day, even without race-car power.

Sadly, I had to sell it soon thereafter. I couldn't afford storage, and I wouldn't let it face a Michigan winter. A Californian bought it. Last I heard, it was repainted the original yellow and was distinguishing itself in local autocrosses.

Sometimes late at night I can still hear the wail of its exhaust... AW

AutoWeek January 20,1986